Introduction

Phased Zonal training (PZT) of which Interval Training is but one example uses the idea of carrying out an activity in different zones of intensity during different phases of a workout. A phase involves the athlete working at a certain intensity for a specified duration or distance. A complete workout is a contiguous series of different prescribed phases.

But what is the point of PZT? Well, if you go out and run the same same distance at the same level of effort each day then you will quite quickly reach a point where you stop improving. Of course if you are happy with this then fine. I was and ran like this for decades, enjoying the aesthetics of running and not being particularly interested in improvement or competition. On the other hand if you wish to compete, to reach your full potential you are going to have to use a different strategy and "polarise" your training. This involves doing a mixture of long low intensity sessions, shorter "tempo" training and highly intense interval training interspersed with periods of rest, cross training, core stability, strength and flexibility training. You will also need to progressively increase the intensity of your training while avoiding injury. Carefully controlling the duration and intensity of your effort with training zones both within and between workouts is essential.

80 20 Running (I strongly recommend reading a copy of "80 20" Running by Matt Fitzgerald which provides both an interesting historic background and the scientific basis of this type of training)

But what are zones? What is their basis? There are numerous schemes available. So many in fact as to overwhelm someone starting out with structured training. What scheme should you choose? Luckily there is evidence that it does not really matter that much. The most important thing is that your training has a structure and is varied. It should both progressively improve performance and avoid injury. For elite athletes however the margin between performance improvement and injury is very narrow indeed and objective measures of the intensity of training are needed.

Some schemes are in my opinion of more value than others. They are discussed below.

Subjective Exercise Intensity "Measures"

RPE Scales

Historically the earliest exercise intensity zones were based on scales of "Rate" of Perceived Exertion (RPE). An example would be the scheme proposed and developed by Borg. (The slightly odd presentation was so the number associated with the description, times ten, approximates to a typical heart rate in a young athlete). Although of value in the absence of a more objective measures and with some evidence of a weak correlation with objective exertion intensities (when compared with heart rate) the scales are overly granular for a subjective measure. They give a sense of precision that is simply not there. Personally I have never felt able to accurately judge my level of effort during 40 yrs of road running. I think most athletes will have on occasion found running a familiar route much harder than usual and then been surprised that it took no more time than usual to complete it. Subjective estimates of intensity are influenced by so many factors including the complexity of the human psyche. I doubt any scheme, however sophisticated, could adequately account for that!

| Perceived Exertion Rating | Description of Exertion |

|---|---|

| 6 | No exertion; sitting and resting |

| 7 | Extremely light |

| 8 | |

| 9 | Very light |

| 10 | |

| 11 | Light |

| 12 | |

| 13 | Somewhat hard |

| 14 | |

| 15 | Hard |

| 16 | |

| 17 | Vary hard |

| 18 | |

| 19 | Extremely hard |

| 20 | Maximal exertion |

I have found the development of objective physiological measures far more useful for my day to day training.

This involves measuring some value that is correlated to exercise intensity. Examples are pace, heart rate and power. For each measure that we use we need to calibrate it to our own performance if it is to help us prescribe exercise intensity. This typically involves finding the maximum steady value that we can sustain for a certain period of time. Once we have this, we can develop a system of zones based on ranges described in percentages of this value. One example from running would be something called Threshold Pace or TP (for the moment ignore the details, it is just an objective datum on which to hang zones). This is usually predicted from the maximum steady pace that we can achieve during a 30 minutes field test.

Objective Intensity Measures

Heart Rate Zones

Heart rate is probably the second oldest objective measure of effort coming after pace. The development of and ready availability of wearable heart rate monitors means that this is often the first objective measure of exercise intensity used by athletes new to structured training. There is something very reassuring about using heart rate. But how do you work out zones of training intensity based on it? There are numerous schemes available, some better than others. Heart rate does however have its limitations which will be discussed at the end of this section.

Maximum Heart Rate based zones.

Polar HR Scheme This is the simplest of schemes and produces zones as percentages of maximum heart rate. An example would be those pioneered by Polar. Although giving training a structure the zones are rather arbitrary and I think are based on the wrong datum, but more of that in a bit.

Heart Rate Reserve based zones.

Karvonen A better scheme is one that takes into account your resting heart rate in addition to your maximum heart rate and works out zones from percentages of the difference (heart rate reserve) between these two values. This was developed by Karvonen. We must be careful to note the same 5 zone descriptions and percentages as above but percentages of something quite different! The Karvonen zones are more tightly packed, spanning just the physiological range in heart rate. This makes more sense. We can see that zones bearing the same labels may represent quite different values.

So if we use Karvonen zones we need to know two things, resting heart rate and maximum heart rate. Resting heart rate is straightforward enough. The problem is how do you find out your maximum heart rate?

Maximum Heart Rate

I have seen athletes confound maximum heart rate with the maximum heart rate achieved during routine training. They are different! The latter is easily available on modern devices but is likely to be quite a bit lower than your true maximum heart rate. If you base your zones on this value you may get an easy ride but may not improve as much as you should.

Formula methods provide an approximation to your maximum heart rate. Some are better than others. None are perfect. The most commonly used (and worst) predicts your maximum heart rate to be:

| 220 - age (in years) |

I believe it is so popular because it is easy to remember and the calculation only requires a simple subtraction. I would not however recommend using this. A better approximation is that developed by Tanaka. It uses:

| 209 - 0.7 x age (in years) |

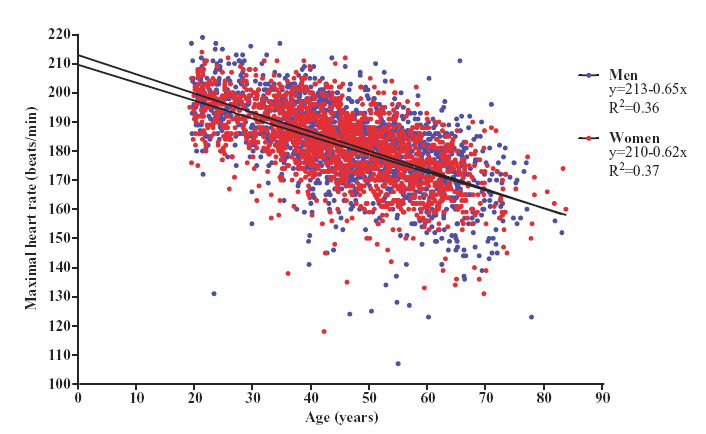

Even better approximations have been developed which also take in to account gender. These approximations are great for predicting the average maximum heart rate for a particular age in groups of people, but not so good at predicting maximum heart in a particular individual. The following plot, from the HUNT Fitness Study, shows why these best fit linear approximations are poor predictors of individual maximum heart rate. For a particular age the spread of actual maximum heart rate values is wide. You are unlikely to rest on the predictive line and may fall far away from it. If you have trained for decades thus reducing the age related decline in maximum heart rate you will almost certainly be an outlier with a much higher than predicted value.

If you are to use maximum heart rate as your datum on which to base your zone values then unfortunately you really need to measure it. This is an uncomfortable and stressful thing to do. You need to be confident that you are in good health. Unless you are young with no adverse family or personal medical history you should consult your doctor first.

So are you stuck with having to actually measure your maximum HR with a field test? Thankfully not, and here is why. There is a much better datum on which to base your training zones. It is one that is applicable across all endurance sports and all measures of performance. It has a sound physiological bases and will ensure your training zones target that which can be improved the most.

Lactate Threshold

The lactate threshold is a supremely important physiological event for endurance athletes. It is the intensity of exercise at which lactic acid levels measured in blood increase sharply on further increasing intensity. This is because if we progressively increase exercise intensity we are no longer able to get oxygen at a sufficient rate to supply all the energy needs of an activity from the oxidation of glucose alone (aerobic metabolism). Additional energy must come from the splitting glucose into lactate (glycolysis, anaerobic metabolism). Note that aerobic metabolism continues maximally but with an increasing additional anaerobic component with increasing work intensity. Although the requirement for energy is met, it comes at a heavy cost. Lactic acid accumulation and associated blood pH reduction limits further activity. It can only be cleared in a process that utilizes oxygen, and so cannot be eliminated until we reduce levels of activity again. (This is known as the oxygen debt). The other problem is that glycolysis is highly inefficient and produces only a fraction (about 1/15) of the energy produced from the metabolism of glucose with oxygen) It is wasteful of your precious glycogen reserves (you don't want to walk the last few miles of your marathon!)

VO2 and VO2 max

VO2 is oxygen uptake in milliliters of oxygen per kilogram and so is a weight independent measure of how much oxygen an athlete is consuming at some point in time. VO2 max is the maximum oxygen uptake possible in a particular athlete during a maximally intense activity.

The graph below demonstrates the relationship between exercise intensity, VO2, VO2 max and blood lactate. The yellow arrow shows the increase in intensity of an activity and so energy consumption. The red graph shows that initially oxygen consumption (VO2) keeps pace and we metabolize glucose aerobically and don't produce an excess of lactic acid. As the intensity increases further we reach the limit at which our body is able to utilize oxygen (VO2 max). As we can no longer match our energy consumption through aerobic energy production we have to get part of our energy from glycolysis and lactate starts to rise. This produces the typical "hockey stick" curve which is seen in the real world graph to the right.

VO2 max and Lactate Threshold

There is clearly a relationship between VO2 max and Lactate Threshold. Above VO2 max any sustained additional energy production must come from glycolysis The reason the VO2 at lactate threshold is not equal to VO2 max is because the switch over to anaerobic metabolism happens progressively below VO2 max. The rate of switchover is something that is very amenable to training as we will see below. We might choose to call the VO2 at which lactate levels start to rise appreciably the VO2 LT (Lactate Threshold). It is somewhat lower then VO2 max.

VO2 max is heavily genetically determined both in its untrained level and its response to training. The typical person can expect a modest maximal increase of up to 15%. But there are much bigger gains to be made. To understand this requires knowledge of the interrelationship between lactate threshold and VO2 max as we get fitter.

Training makes lactate elimination more efficient. This means that blood lactate is lower for a given intensity of exercise below VO2 max. Of course this reduction in lactate for a particular exercise intensity must ultimately fail as we approach and then exceed VO2 max and so perhaps frustratingly eventually bump up against our own genetic limitations.

The biggest improvements in performance for most endurance athletes stem from being able to get close to and sustain activity just below VO2 max, and to do so without rapidly metabolizing glucose (and therefore their glycogen reserves). This improvement is as a result of the change in shape of the lactate curve which increasingly develops the so called "hockey stick" with lactate levels only rising when close to VO2 max. The recovery of lactate is an oxygen consuming process and so in part the modest increase in VO2 max with training results from the improvement in lactate metabolism. Representative lactate plots vs. %VO2(max) of an untrained and a trained athlete are shown above right for comparison.

To demonstrate this I have produced this animation with VO2 on the x axis and blood lactate on the y. The left hand vertical red line indicates VO2 at LT and the right hand one VO2 max. The purple line represents lactate threshold blood lactate. The time element for the animation could be considered the time into your training plan as you progressively become fitter. VO2 max increases a little with training and this moves the whole lactate curve to the right. VO2 LT moves more dramatically to the right influenced by this shift and the increasing bend in the curve as lactate elimination improves. The VO2 LT datum is far more relevant to endurance athletes and typically an activity of this intensity can be sustained for around half an hour which, for many runners, is long enough to complete a 10k race. This is where most of the gain in athletic performance for an endurance athlete comes from and this is why the lactate threshold is such an important value on which to base our training zones.

What about MLSS, OBLA, AT, VT etc...

Of course a plot of lactate vs. intensity of activity (power, flat pace etc...) does not have a "point" where lactate suddenly starts rising. It is a curve, though admittedly with a hockey stick shape which is more noticeable in a trained athlete. We can look at a curve and say - yep - it really starts rising quickly there but if we are to ascribe this to a certain intensity level we need a rule to find a point on the curve. To do this we need a definition. This is where things get messy as there is no single definition! There are at least 20 different definitions of lactate threshold in published research and a multitude of synonyms to describe these. We might choose a threshold level of lactate but then which level? Lactate at rest hovers around 1 (mmol/l). Definitions using a threshold level seem to range from 2 to 4. These assume that the level of lactate has reached a constant value at a particular steady exercise intensity (and so measurements are taken after a suitable delay following changing to this intensity).

But we can then choose to bring in a time element and define the lowest intensity where blood lactate does not reach a steady level but continues to rise. This is described as the Onset of Blood Lactate Accumulation or OBLA. Conversely, less than a hair's breadth below this, is the Maximum Lactate Steady State or MLSS. (Though conceptual opposites, the intensities defined in this way are in truth the same, any differences resulting from measurement). Some authors use the concept of OBLA (and so MLSS) to define lactate threshold and this is my preferred definition as it is less arbitrary than choosing a particular level (definitions of which vary because it is an arbitrary choice). Lactate threshold defined in this way will correspond to a higher work intensity than using a simple steady state threshold level.

But what about all the other thresholds? Anaerobic Threshold (AT) is merely a synonym of Lactate Threshold. The Ventilatory Threshold (VT) is the "point" at which the graph of ventilation vs. work intensity quickly steepens. It does so because, in addition to the CO2 from aerobic metabolism, CO2 is also produced from the buffering of lactate from anaerobic metabolism by bicarbonate. It is therefore merely a surrogate for the lactate threshold.

So we see that there are really only two types of definition of lactate threshold. One is based on a particular (arbitrary and variable) threshold value of a steady state blood lactate. The other is based on the presence or absence of a steady state level of blood lactate. The other definitions are either synonyms or surrogates of lactate threshold. The difference between lactate thresholds derived using these definitions will reduce with training as the curve becomes increasingly hockey stick shaped and so becomes decreasingly relevant. The vast majority of people will in any case use a field test or even historic data and algorithm to estimate their lactate threshold. From a practical training point of view, I believe they can be considered to be the same.

Training Variety and Lactate Threshold

Of course training and improving the efficiency of lactate elimination is not the only element of training. We also need to do activities that improve our strength, core stability, flexibility, endurance and efficiency. We need to train our neuromuscular system. We need train ourselves to tolerate a degree of discomfort as this is invariably present in competition. These are all necessary, but without training the lactate system, these would of themselves be insufficient for success in fast endurance activities.

We also need to know where our lactate threshold is in order to avoid it! Training near lactate threshold and also the avoidance of training near lactate threshold are both crucially important to polarized training. Having a system of zones of intensity that are based on a reasonably current and representative field test of lactate threshold allow us to do this with confidence.

|

|

| Easy Long Run (with Dogs!) | Hard Run (Cardiff 1/2 Marathon Race) |

Lactate Threshold vs. FTP, rFTPw, LTHR etc...

But what about all the different threshold values out there? Pace, heart rate and power for running, cycling and swimming? Well, they are all doing the same thing. The thing to keep in mind throughout this apparent complexity is that there is only one physiological event taking place in us as we reach lactate threshold. We just have to calibrate each sport and metric combination relative to this. (In fact, for convenience, for a particular sport, we can obtain LT HR, LT Pace, LT Power all in one go during a field test)

Methods for Determining Lactate Threshold

OK. How do we find out our lactate threshold?

Measure Directly

Of course the gold standard would be to measure blood lactate and our metric of interest (HR, pace, power) while doing a particular activity (run, bike, swim) as we progressively increase activity and find the point where blood lactate starts to sharply increase. This is typically done in a laboratory along with measurement of VO2 max. In reality few people have access to these tests routinely. As our lactate threshold can increase quite quickly early on in training and we would have to keep revisiting this process periodically as the precise values produced would lose relevance to our current state of conditioning.

Estimate with a Field Test

Fortunately there are field tests that can give estimated values that are very well correlated with laboratory measured values. We can also do them every few weeks as our training progresses to recalibrate our training zones.

After a suitable warm up you merely need to start a workout and maintain a constant maximum effort over 30 minutes in your chosen sport. This is because 30 minutes has been found to be the maximum time that most athletes can keep parked on their lactate threshold during an activity without flagging. It is important to try to keep a constant maximum pace during the test, hard but this comes with practice. For a particular sport do this with all your sensors so that you can assign a threshold value to all of them in one session. Virtually every watch website allows you to get the average heart rate, pace or power during a selected thirty minute interval, and with the exception of heart rate, this provides your threshold value.

So if we were to do this successfully for running with a gps watch, a heart rate strap and a Stryd foot pod we could at once find out our running threshold pace, heart rate and power. Unfortunately the terminology is not consistent between measures and sports. We have TP (threshold pace), FTP (functional threshold power) and LTHR (lactate threshold heart rate). These can be prefixed with the sport and post-fixed with the unit of measure, so rFTPw is Jim Vance's running functional threshold power in Watts (I guess it is a sub-scripted capital W). The important thing is not to get hung up on the terminology but rather to understand the underlying concept.

Lactate Threshold Heart Rate - LTHR

Because heart rate lags behind changes in activity intensity it is customary in a 30 minute field test to discard the first 10 minutes of readings. You do a 30 minute test but it is the average of the last 20 minutes that is used to estimate LTHR.

The Non-Linearity of Heart Rate in relation to Exercise Intensity and Duration of Activity

Heart rate above resting heart rate exhibits an approximately linear relationship to exercise intensity (running pace, cycling power) in most but not all people. Sigmoidal responses are seen. There is frequently, though not invariably, a deflection point which may correspond with lactate threshold (Conconi). The problem is the scale gets rather squashed as we approach maximum heart rate and our lactate threshold heart rate may only be 10 - 20 beats lower than this leaving little dynamic range to describe intensity above threshold. If we combine these problems with the slow response of heart rate to sudden increases or decreases in training intensity (of the order of 20-30 seconds) and the slow drift up of heart rate at the same training intensity beyond 10-30 minutes, we can see that the range of usefulness is really very limited.

It is easy to see some of the limitations of using heart rate. If we attempted to keep a constant heart rate during a phase of activity we simply could not achieve this in the first 20 to 30 seconds. It is therefore not of value for short intervals. If we kept it constant over a longer phase we would be working harder at the start and have an easier time towards the end of the phase.

Estimate from Accrued Ordinary Workout Data

Many sports watches and some foot pods use third proprietary algorithms to predict lactate threshold and other quasi threshold metrics from routine data. Examples are Firstbeat used on a variety of watches including Garmin, Coros's Evolab and Stryd's auto-CP. Typically they would use a model such as critical power or speed (see the critical power section below) to predict these. Such a model needs a sufficient quantity of variable durations near to intensity limits data to really work and without this any prediction will be inaccurate. These results are typically given as a single value rather than a range (to reflecting the uncertainty in prediction) and we should be wary of information arising from a complex model presented in this way. It is better that we know what we don't know!

Zones, Zones and More Zones

There are a large number of zone (zonal) systems out there resulting from combinations of activity type, metric and authority (coach, sporting organisation, equipment provider). Each zone is a range of prescribed training intensity. To have any meaning they need to be related to some measured significant physiological datum in the athlete and are expressed as percentages of this datum. In endurance sports it makes most sense to relate these to Lactate Threshold.

If we compare the following two examples, lactate threshold zones from different authorities:

| Zone | rFTPw % |

| 1 | 70 - 80 |

| 2 | 81 - 90 |

| 3 | 91 - 100 |

| 4 | 101 - 115 |

| 5 | 116 - 130 |

Although sharing the same common structure, zones as ranges of percentages of a threshold value, they are rather different. Running at the very top of Stryd zone 3 would be running right on your lactate threshold whereas cycling at the very top of Joe Friel's zone 3 detailed above would be significantly under lactate threshold.

| Zone | LTHR % |

| 1 | < 81 |

| 2 | 81 - 89 |

| 3 | 90 - 93 |

| 4 | 94 - 99 |

| 5a | 100 - 102 |

| 5b | 103 - 106 |

| 5c | > 106 |

Critical Power

Critical PowerI feel that I should now discuss critical power. This is a fascinating concept as, unlike lactate threshold, it merely observes performance without any need for a metabolic correlate. It works like this:

There is a threshold intensity of training, the critical power, below which there is no time limitation of activity. Above this threshold, training is time limited. The more intense the training above this threshold, the shorter the possible duration of activity. It can be shown that a very simple equation describes this relationship, which is commonly referred to as a power curve, and is stated below.

| t = |

|

wa is a constant value with units of energy and could be thought of as representing some depletable anaerobic reserve metabolism. We might give this a name, say anaerobic reserve energy ARE. To originally demonstrate that in general the form of the above power curve was correct would have required multiple tests to exhaustion at different intensities. Luckily to estimate the the power curve in an individual athlete requires just two tests to exhaustion separated by a suitable recovery period. (of course a result from a linear regression of more tests is more likely to reflect your true CP and many people recommend 5 - ouch!). We can see this easily if we re-arrange the equation:

| p = |

|

+ | pc |

We just need to fit a line between these points. The gradient is wa and the intercept pc. OK, so we might not be keen to do two constant power efforts to exhaustion at two different power levels to determine our current power-duration curve.

Luckily modern watch and web site technology allow an individual to accumulate a large data set of power and duration data pairs. The upper boundary of these, if recent enough, indicates the general shape of your power curve. It has to be realized however that in general this upper boundary of all these data pairs will be lower than your "true" power curve. This is because from your everyday training you may not have sufficient maximum effort-duration data pairs at all intensities to fully flesh it out and of course any effort-duration pair is in the context of a complete run and therefore cannot utilize all anaerobic reserve energy or you would stop! The above shows my running power curve over several years. It was only in 2019 that my training was varied enough (a structured training plan with very short intervals, short intervals, longer intervals, tempo runs, long steady runs and recovery runs as per 80:20 running) to push the curve out towards my probable true power curve. However derived, if I have a good estimate of my power curve, I can interpolate a value for a duration of 30 minutes. This value corresponds to my lactate threshold.

For a steady power of 60 minutes or more in duration the theoretical power-duration curve is very close to the horizontal plot of CP. This has, therefore, been chosen as a surrogate of CP but it will be a slightly higher value. To muddy the waters further this is variously described as CP or Functional Threshold Power - FTP. FTP is a misnomer as it is not a threshold as it is neither CP nor power at LT. If we accept this definition of FTP it must, from the concept of critical power and the basis of field tests of LT, be lower than power than power at LT.

It would be good to have a simple descriptive system to describe predicted or measured steady state power-duration values rather than a plethora of confusing and ambiguous terms.

- P∞ true critical power - CP

- P60 functional threshold power - FTP (also incorrectly referred to as critical power - CP

- P30 lactate threshold power - LTP

The Limitations of the Critical Power Concept

It is easy to see that this idea fails for very short efforts. The power curve values are simply unrealistically high and approach infinite power as the duration approaches zero. This is nonsense. It is obvious that there is an upper limit of power output related to strength and neuromuscular conditioning. It is also clear that on very long runs we eventually stop because we are exhausted not because we have exhausted some anaerobic reserve capacity. The relationship breaks down at the extremes of both very short and very long durations.

Critical Flat Speed

There is linear relationship between power and speed when running on the flat S = k × P. From this it can be seen that there must be a critical speed, just as there is a critical power Sc. There must also be an anaerobic reserve distance Da or ARD! So for a race of distance Dr we can state:

| Dr | = | Sc | × | tr | + | Da |

This is simpler than a power curve, a straight line. One way to think of this is that we cover the race distance with the product of the race duration times our critical speed combined with our anaerobic reserve distance! Two flat races at different distances are an ideal way of finding your critical speed and anaerobic reserve distance. If we plot recent race distances vs. duration, a fitted line will have a slope of Sc and intercept of Da. From this line it is easy to interpolate your lactate threshold speed (30 mins duration) and also predict your race duration for a flat race at another distance.

| t2 | = | t1 | × |

|

This differs from Peter Riegel's formula:

| t2 | = | t1 | × |

|

1.07 |

The formula based on critical flat speed and anaerobic reserve distance under-estimates race times for longer distances such as the marathon. It also makes absurdly fast predictions for very short distances of say 400m or less. The Riegel formula over-estimates time for short distances of around 1500m.

My most recent race distances are a half-marathon in 113 minutes and a 10k in 53 minutes. It is easy to see that my Sc = 11 km/h and my Da is just 0.283 km. I can predict a 5k time of 25 mins 12 seconds and 1500m time of 6 mins 38 seconds. It is interesting that my anaerobic reserve distance is less than 1/3 of a kilometer but this would give me a predicted 400m time of 38s which would easily make me a world record holder!

Don't Mix Things Up

Of course each authority is keen to promote their zonal system as best. In reality there is no good evidence to promote one scheme over another. I think the main thing to consider is if you choose to use a training plan from a particular coach you need to use his zone scheme too. To not do so would be, by analogy, the equivalent of transferring a tune, note for note, line by line, into a different musical scale. It probably wouldn't sound good!

In reality you might undertrain or worse overtrain and injure yourself.

Now Mix Things Up

We have covered the physiological basis of training zones and how, for endurance athletes, the best choice of basis for these is lactate threshold (pace, power, heart rate). With this objective basis we can reliably know where the intensity of our training is positioned in relation to this important datum. It allows us to both target lactate threshold and just as importantly to avoid it. It allows us to calculate our training load from a wide variety of activities. This informs our future training.

.